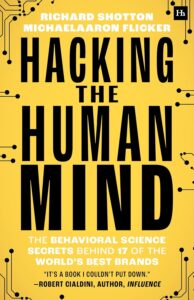

Hacking the Human Mind authors Richard Shotton and MichaelAaron Flicker reveal ways brands exploit human psychology and how we can use this to our benefit!

What We Discuss with Richard Shotton & MichaelAaron Flicker:

- Five Guys built a $1.6 billion empire on a single insight: doing one thing exceptionally well signals expertise. The company’s refusal to add chicken, salads, or ice cream is strategic proof that specialization creates perceived mastery in the consumer’s mind.

- Counterintuitively, the “goal dilution effect” shows that adding more benefits to your pitch actually weakens it. When tomatoes were described as preventing cancer and improving eye health, people rated the cancer benefit 12% lower, suggesting that focus beats feature-stuffing every time.

- As a species of “cognitive misers,” our brains evolved to conserve energy, so we rely on mental shortcuts rather than deliberate analysis. Brands that understand these heuristics work with human nature instead of against it, making persuasion feel effortless rather than forced.

- Environmental cues shape our experiences more than we realize. Classical music makes wine taste more expensive, heavier cutlery makes food seem more premium, and tempo controls how fast we eat. Our senses are constantly being orchestrated without our awareness.

- Next time you’re pitching yourself or your idea, resist the urge to list every qualification and benefit. Pick your strongest single message and let it breathe. Your audience’s brain will reward clarity with credibility, turning restraint into your most persuasive tool.

- And much more…

Like this show? Please leave us a review here — even one sentence helps! Consider including your Twitter handle so we can thank you personally!

Behavioral scientists Richard Shotton and MichaelAaron Flicker take us deep into this hidden world of persuasion in their book Hacking the Human Mind: The Behavioral Science Secrets Behind 17 of the World’s Best Brands. Richard and MichaelAaron reveal how Five Guys built a $1.6 billion empire by doing less, not more — proving that specialization signals expertise in our shortcut-loving brains. They unpack the “goal dilution effect,” showing why cramming extra benefits into your pitch actually undermines your strongest selling point. The conversation ventures into sensory manipulation territory too, exploring how classical music makes wine taste more expensive and heavier cutlery elevates our perception of food quality. Whether you’re a marketer looking to ethically apply these insights, a consumer wanting to understand what’s influencing your choices, or simply someone fascinated by the quirks of human cognition, Richard and MichaelAaron offer a roadmap to working with human nature rather than against it. Listen, learn, and enjoy!

Please Scroll Down for Featured Resources and Transcript!

Please note that some links on this page (books, movies, music, etc.) lead to affiliate programs for which The Jordan Harbinger Show receives compensation. It’s just one of the ways we keep the lights on around here. We appreciate your support!

- Sign up for Six-Minute Networking — our free networking and relationship development mini-course — at jordanharbinger.com/course!

- Subscribe to our once-a-week Wee Bit Wiser newsletter today and start filling your Wednesdays with wisdom!

- Do you even Reddit, bro? Join us at r/JordanHarbinger!

This Episode Is Sponsored By:

- SimpliSafe Home Security: 50% off + 1st month free: simplisafe.com/jordan

- Rag & Bone: 20% off: Rag-Bone.com, code JORDAN

- Progressive Insurance: Free online quote: progressive.com

- Homes.com: Find your home: homes.com

Thanks, Richard Shotton & MichaelAaron Flicker!

Click here to let Jordan know about your number one takeaway from this episode!

And if you want us to answer your questions on one of our upcoming weekly Feedback Friday episodes, drop us a line at friday@jordanharbinger.com.

Resources from This Episode:

- Hacking the Human Mind: The Behavioral Science Secrets Behind 17 of the World’s Best Brands by Richard Shotton and MichaelAaron Flicker | Amazon

- The Behavioral Science for Brands Podcast | The Consumer Behavior Lab

- MichaelAaron Flicker | LinkedIn

- Richard Shotton | LinkedIn

- The Surprising Behavioral Science That Built Five Guys: Goal Dilution | StartupNation

- How Mac and Cheese Became an All-American Dish | Weird History Food

- Pareidolia: What It Is and How to Exploit It in Marketing | Bryan srl

- The Unhealthy = Tasty Intuition: Are You Under Its Subconscious Influence? | Psychology Today

- Push Veggies With Tasty Language | SPARQ

- Predicting Hunger: The Effects of Appetite and Delay on Choice | Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes

- Starbucks’ Pumpkin Spice Latte and the Scarcity Principle | The Shop

- Scarcity and the Effect It Has on Customers’ Buying Habits | Userism

- Nostalgia Weakens the Desire for Money | ResearchGate

- Celebrating 90 Years of KitKat Breaks | Nestlé Global

- Case Study: How Fame Made Snickers’ “You’re Not You When You’re Hungry” Campaign a Success | Campaign

- Don’t Just Target an Audience, Target Their Mood | Marketing Week

- To Create Strong Memories, Use Concrete Language | Marketing Week

- Hit Makers: How to Succeed in an Age of Distraction by Derek Thompson | Amazon

- A Faux Physical | AND ORS

- Why $9.99 Feels Cheaper Than $10—and Other Pricing Tricks That Actually Work by Hey_Emon | Medium

- Inside the Wacky History of Häagen-Dazs and Its Made-Up Name | People

- The Invention of the Chilean Sea Bass | Priceonomics

- The Red Bull Firm’s Pricing Strategy Analysis | StudyCorgi

- Baba Shiv: How a Wine’s Price Tag Affects Its Taste | Stanford Graduate School of Business

- How Guinness Uses a Weakness to Emphasize a Strength | The Behavioral Science for Brands Podcast

- Runaway Jury | Prime Video

- How Dyson Uses the Illusion of Effort to Set Expectations of Excellence | The Behavioral Science for Brands Podcast

- Sensehacking: Revealing the Power of the Senses with Professor Charles Spence | Nudgestock

1273: Richard Shotton & MichaelAaron Flicker | Marketing to Human Minds

This transcript is yet untouched by human hands. Please proceed with caution as we sort through what the robots have given us. We appreciate your patience!

Jordan Harbinger: [00:00:00] Welcome to the show. I'm Jordan Harbinger. On The Jordan Harbinger. Show, We decode the stories, secrets, and skills of the world's most fascinating people and turn their wisdom into practical advice that you can use to impact your own life and those around you. Our mission is to help you become a better informed, more critical thinker through long form conversations with a variety of amazing folks, from spies to CEOs, athletes, authors, thinkers, performers, even the occasional mafia enforcer, rocket scientist, or legendary Hollywood filmmaker.

If you're new to the show or you want to tell your friends about the show, I suggest our episode starter packs. These are collections of our favorite episodes on topics like persuasion and negotiation, psychology, geopolitics, disinformation, China, North Korea, crime, and cults and more. That'll help new listeners get a taste of everything we do here on the show.

Just visit Jordan harbinger.com/start or search for us in your Spotify app to get started. I'll be honest, I've read a lot of business books and case studies, and most of them, they just kind of blur together after a while. But this book that I read for the show today, there's stuff [00:01:00] in here I genuinely never heard before, such as Why Five Guys, the burger joint, refuses to do more than one thing and somehow makes more money doing less. Why calling something healthy food, mainly, can make it taste worse in your brain. Why? Kraft sells a million boxes of mac and cheese per day. And yes, that number is as upsetting as it sounds today. We're talking about the hidden psychology behind why we buy what we buy, why our brains take shortcuts, and how brands quietly manipulate those shortcuts every single day, sometimes brilliantly, sometimes hilariously.

Joining me today are Richard Shotton and MichaelAaron Flicker. Yes. Two guests at the same time today. I know that's a rare one, and by the end of this episode, you're never going to look at grocery stores menus or Starbucks seasonal drinks the same way ever again. Here we go with Richard Shotton and MichaelAaron Flicker.

I have to admit, I've read a lot of business case studies in my life, right? Because I used to love doing podcasts about business, less so these days. But there's a lot of stuff in the book that I just never heard before, and [00:02:00] some of it's quite fascinating. You know, looking at new products or the nostalgia of what it does to marketing is pretty incredible.

So I want to start with Five Guys burgers, one, because I've eaten there one time in my entire life and it was so good. It's so good that I haven't gone back because I know if I go back, I'm going to keep going back and it's going to be a problem. So they do one thing beautifully, and that's kind of their motto, and I'd love to discuss that because if you go to McDonald's, they have everything now.

It's actually kind of overwhelming in some locations.

MichaelAaron Flicker: Yeah, and you know the story that backs up how they got to this insight, Jordan, really helps paint the picture of the bias that they ended up exposing. So I'll paint the picture for you and then maybe Richard, you want to knock down some of the science behind it.

But 1986 we have the founder Jerry Morell, is at the Maryland boardwalk with four of his sons and they're walking down the boardwalk and they're deciding if the oldest son is going to go to college or start a his first [00:03:00] company. And as they're talking, they look across the boardwalk and they see that only one of the stalls has a line triple, quadruple the length of all the other lines.

And the name of the stall is called Thrasher Fries. And they're talking about how could this one place that only does fries. Be so much more popular than all the other places that serve all different types of food. And it's Jerry that gets the credit for having the insight. Maybe it's because they only do one thing really well.

They must be experts. They must be so good at it that it's worth queuing up and waiting for that line. And so today, many years later, Jerry and his four sons become the original five guys. They're a global franchise. They have $1.6 billion in sales, 1800 stores, and they only do burgers and fries. They don't do chicken, they don't do salads, they don't do ice cream.

They only do burgers and fries. And what's so fascinating is that people tend to [00:04:00] believe a product is less effective when it claims to do lots of things. And so when you compare it to only doing one thing, well, it's more believable. That's not just a story. There's a bunch of science to back it up.

Jordan Harbinger: Tell me about the tomato study.

Richard Shotton: Yeah, so this is from the University of Chicago and it's run by two psychologists, Zang and Fishback. And what they do is they recruit a group of people and they give one group a bit of text, which explains tomatoes are brilliant for reducing the probability of cancer. And then that group are asked to say how good you think tomatoes are as part of your diet for reducing cancer.

They get their answer and then they get a new group of people. They show them exactly the same text about cancer as the first group. But alongside that, they also give that second group a bit of information about why tomatoes are really good for your eye health. Now, when that second group are asked to rate how good tomatoes are for preventing cancer, they score tomatoes at 12% [00:05:00] less than the original group.

So exactly the same information, the same facts, the same logic is rated worse if there's that second idea added on. So the psychologist call this the gold dilution effect?

Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. You know, it's funny 'cause right before I hit record, I said, Hey, I read the book. I've got more notes than usual, so I need you to be medium winded, not too short.

'cause then it's like, well wait a minute. What's going on? Not too long, because then we do one example in 12 minutes and I end up one 10th the way through my notes. This is almost the same thing, right? It's like, okay, what do tomatoes do? They prevent cancer. I like it. It's simple. Good. All right. Medium winded right?

Don't tell me about the eye benefits. Don't tell me it's going to get rid of my, the warts I have on the bottom, my, my plantar fasciitis, whatever. I don't want to hear about it. I just want to know about the big one. Tell me the big one and then I'll eat the tomato.

Richard Shotton: And it's very, very different from how most people.

And how most brands behave. Most brands try and cram in lots of reasons about why they're amazing. Most people going to an [00:06:00] interview will try and persuade the interviewer that they've got a million different skills. Sanger Fishback say, look, be really careful before you do that. Each additional reason you add on will undermine belief in the core reason to believe.

Jordan Harbinger: That's quite interesting. I think this goes down to the principle, and you note this in the book, that humans are cognitive misers. We don't want to expend too many resources to come to a decision, and so the brain takes shortcuts, and that's where we end up with cognitive biases. Like this is the most recent thing you heard, so you believe it more.

And it's like, yeah, I don't have to try hard to remember it, for example. Right? These shortcuts that our brain takes. And so brands that harness these shortcuts can bring a lot of success.

Richard Shotton: That's exactly it. The argument from psychologists is that from an evolutionary perspective, energy is a very scarce resource, and thinking is energy intensive and it's effort.

So for most decisions people make, especially commercial ones, most people don't make them in a fully deliberative thought through way. Most of decisions are made in a very [00:07:00] quick snap, reflexive way, and the way that we make these quick decisions is to use what psychologists call heuristics or biases. We have this series of rules of thumb in our head for making really fast decisions, and what's interesting for anyone who is trying to persuade others to change their behavior is these rules of thumb are prone to biases.

Essentially, if you know about these biases, and that's what behavioral site's, catalogs. You end up working with human nature rather than against it. And that's always more effective.

Jordan Harbinger: So this episode is essentially going to be some of these biases, how brands have leveraged them and how we're falling for them every single day, which is kind of, I like this 'cause it's going to have us look at things differently.

And one of the examples that you gave early in the book was Kraft, I think they call it Kraft dinner, which is ambitious, but it's Kraft mac and cheese. Sometimes you eat it for lunch. I don't know why they're so hell bent on dinner, but this sells a million boxes a day. Gross. Sorry. Obviously this episode is not sponsored by Kraft.

I'll eat it, but a million [00:08:00] boxes a day? Someone's buying a lot of this stuff, man. Why not Just why are they buying it? But how did this become so popular? How are they leveraging our psychology to trick us into eating this stuff?

MichaelAaron Flicker: Kraft has a fascinating history. It starts in America, but globally it is seen as one of these nostalgic foods.

Uh, and it starts when a salesman packets together dried cheese. Rubber bandit to boxes of macaroni, and that's the origins of Kraft Mac and cheese. It was during the depression. It was a low cost food staple, and so it comes out of the depression with a lot of positive associations where you could get two boxes of Kraft macaroni and cheese for one of the food stamps during the war days.

And so there's already a natural association within America that there's something emotionally tied to it.

Jordan Harbinger: But here's the thing though, it's like the wrong emotions and maybe that doesn't matter. Maybe that's a big takeaway because if you're like, Hey, remember the poorest you ever [00:09:00] were and you thought you were going to get annihilated by the Nazis or by the economy or by the Soviets, don't you want to experience that again?

Here it is. It's like not really. My buddy, he's a contributor to the show. He can't eat turkey burgers. It's been like decades. And he can't eat turkey burgers because his dad was a, an iron worker and when his dad hadn't worked, they always had to buy turkey burger 'cause they couldn't afford beef or something like that.

And he's like, I can't even smell turkey burger. But part of that is they had it so much, but he's also like, but I also got yelled at during that time my dad was like drinking. During that time, people got in fights a lot around me during that time. It's all, it's all negative association. Kraft has somehow went, Hey, remember when you were poor and war was looming?

Here's that slice of happy. That they've associated themselves with that. So it's kind of brilliant somehow.

MichaelAaron Flicker: Yeah, I would say that humans make decisions. They think they make a lot of logical decisions. I'm going to buy this dinner because Kraft tells me it has 17 essential vitamins and minerals is

Jordan Harbinger: what say.

It does not probably have that, any of those, by [00:10:00] the way.

MichaelAaron Flicker: But we're more emotional than that. The story that your friend tells just proves the fact. Actually, there's a lot of things that have nothing to do with the brand that drives that emotion, that makes you make the decisions. You make ingeniously the box design of Kraft takes that elbow macaroni and turns it upside down so that when you look down the aisle, you're walking down the aisle of all the different macaroni dinners that you could have.

You are much more likely to stop and look at Kraft Macaroni and cheese because it looks like a smile looking back at you. And that's a science, a behavioral science insight called paradolia. But it gives them an edge. All their competitors don't have. So to the point that there is things going on besides just, I want a nutritious meal, I want a delicious tasting meal, there's more driving your purchase decision than just the rational, just the logical,

Jordan Harbinger: the paraia thing is interesting 'cause it, it, since it looks like a phase, it [00:11:00] grabs your attention, which you need if you're walking through a grocery aisle and there's 400 things in your field division at any given time, and they're all brightly colored, right?

So you look at this blue and yellow box and it's got a smiley face on it and it's like, oh, there's this familiar thing. You might even just grab it based on impulse.

Richard Shotton: Absolutely. And with all these points and behavioral science, it's not Michael Aaron and I speculating. There's always experiments that back it up.

And there's a lovely experiment by Guido that proves this. So he did a super simple thing. He shows people pairs of ads and he uses eye tracking to see which of the two ads they look at. What always happens is one of the pairs has a olian image, says something that looks a little bit like a face. It could be the a tree stump or a cloud, but it looks a little bit like a face.

And what he finds is that 80% of the time people pay more attention to the ad that has this olian image. And his argument is it's about evolution. We are the descendants of people who are very quick at recognizing faces. [00:12:00] 'cause faces often meant danger. And if you just snap decision spotted that a few seconds before other people, you had an advantage.

So we are hardwired to spot these face like patterns very, very quickly.

Jordan Harbinger: That makes a lot of sense. The evolutionary argument, actually, I love these kinds of things. I don't know, there's something about this where it's like you, you're decoding what's, these programs deepen our brain, right? Like you're programmed to look at faces.

We're programmed to see patterns where there aren't any because it might've kept you alive a million years ago as a prehuman. It's just really fascinating. Another thing that doesn't make sense for the prehuman, I suppose, but we perceive things we think are healthy to taste bad, so. Why do you think that is?

And second of all, I mean, brands using this, there's a million examples. I just think it's, it's kind of funny that we have to trick ourselves like this,

Richard Shotton: and this is one of those experiments that varies by culture. So absolutely in America there is an association that healthy foods are poor [00:13:00] tasting. So there's a lovely study by guy called Ragin, who's at McCoon School of Business, and he gets a group of Americans together, serves them, an Indian buffet, loads of different foods, and gets the diners to rate how much they like each of the items.

They rate the naans, the Bolty, the Lassi, the Indian yogurt drink. Ragin doesn't care about any of the results apart from what people say about the Lassie. He's just asking lots of questions as a bit of a smoke screen. But when it comes to the yogurt, drink the Lassie, sometimes he tells diners it's an Indian health drink.

Other times he tells them it's an unhealthy Indian drink. And what Ragin finds is that the people who think it's unhealthy, they rate that drink 55% better than the people who think it's a health drink. Because what's happening here is people through experience have generally discovered, you know, matcha tea, I don't know, or some other health craze.

It tastes horrible.

Jordan Harbinger: Oh, don't tell my wife, she loves matcha. I think [00:14:00] it tastes like,

Richard Shotton: okay, freaking, maybe the poor example

Jordan Harbinger: green. You know, it tastes like some vegetables, period. Yeah, no,

Richard Shotton: it tastes like the underside of a, a lawnmower. I've heard people say,

Jordan Harbinger: oh, the underside of a lot of things. Let's leave that one there.

Richard Shotton: It's essentially, people have learned that generally unhealthy things don't taste very nice. And then they apply that rule even when it's irrelevant. Even in like Han study, people are trying the same products, but it's that label that changes their perceptions.

Jordan Harbinger: I guess I should ask you, is the opposite true?

So if I make broccoli and I press it into hot dogs, sounds so gross, but like if I take, this is a terrible example, Brussels sprouts and broccoli, and I make it look like a slice of pepperoni pizza, is that going to make it look more appetizing despite the fact that it's a green slice of pizza?

MichaelAaron Flicker: I think if you can prioritize the indulgent aspect of that broccoli and brussel sprouts.

I see sweet sizzling Brussels sprouts, hot tangy. If you can get to the indulgent side, what the science shows is, [00:15:00] compared to focusing on it being healthy or just plainly describing it. It's always going to do better. The science shows it will do better.

Jordan Harbinger: Okay. And then if I want to sell health food, do I focus on the opposite?

Do I say like, look, we got broccoli, it's fresh, it's uh, I don't know, loaded with antioxidants. It was grown in the back of the restaurant on the farm. I suppose I'm answering my own question here, because that's how all that stuff is marketed. Yeah.

Richard Shotton: The issue with how healthy stuff is marketed is that people focus on the health part.

Just because something happens to be healthy doesn't mean that's the aspect that is best at persuading consumers to buy it. There's a lovely study from Stanford running a real cafeteria where a guy called Bradley Termil alternates the labels on the broccoli. So sometimes he'll say, as Michael Aaron said, light and low broccoli.

Sometimes he'll say Sweet sizzling broccoli. So sometimes he's talking about the health benefits. Sometimes he's talking about the taste. And they sell 41% more of exactly the same food. [00:16:00] When it's the taste in that's emphasized, not the healthiness. It's a simple thing ERs could do is stop focusing on health and start thinking about emphasizing the enjoyment.

MichaelAaron Flicker: And Jordan here is a real mind bender when they focus on low fat, low carbs, zero sugar. That's actually going against what could be better for them. Right. When you focus on the negative of something, it actually inserts the wrong thing in people's minds.

Richard Shotton: Yeah. You're just setting it up like zero alcohol or calorie free.

You're emphasizing the deprivation. That comes with this purchase, you should be emphasizing the indulgence.

Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. So instead of my green juice, maybe I'll have a chicharone smoothie in the morning. Yeah, yeah. Indulgent indeed. Let's talk about preferences, because you mentioned future preferences are different from what we perceive that we want now, and there's an experiment about this.

I, [00:17:00] I love this one because I actually ended up doing this to myself by accident over the last few years. So on airplanes, they'll email you and they'll go, Hey, do you want the grilled chicken with asparagus? Or do you want the, I don't know, pepperoni abomination that the chef has made that, you know, it sounds way better, but is definitely a thousand calories.

I'm like, all right. Grilled chicken with asparagus, I guess. And then you're on the plane and you're like, Ooh, that pizza thing smells good. Ah, I already picked the chicken, but I, I want to hear the science behind this.

Richard Shotton: You're not the only one that that does this. This is a widespread finding, so it's a British experiment from a guy called Daniel Reed.

1998 study when he was at Leeds. And he goes out to an office and he gives people an offer. He says, look, do you want a candy bar or an apple? They're both free. You just get to pick one. And to some people, he says, you choose now and I'll come back in a week's time and give you your snack. And when he sets it up like that, the apple and [00:18:00] the candy bar are equally preferred.

50 50 split. Other people, same offer Candy Bar or Apple. But he says, pick your one snack and you have it now. And when he does that, there is a massive swing towards the candy bar. You've got 81% of people picking candy bar, 19% picking Apple. If people pick for their future selves, they pick in the way they think they should behave.

If people pick for now, they pick in a way that just satisfies their base desires. So you've gotta think as a marketer or as anyone trying to persuade someone else, which of those two reasons are going to work best in my favor. If I'm selling a health food, try and reach people when they're doing their online shop and it'll be delivered in two months time.

If you're sign trying to sell crisps, get it at that immediate point of purchase.

MichaelAaron Flicker: What I would add to this, Jordan, is if you are trying to ask yourself how to live a healthier life, thinking about when you make snap decisions in the moment when you're hungry versus planning your meals, [00:19:00] even just for the next day, you are likely to make better choices for yourself, even if you require yourself to pick the meal, even just the day in advance, because your future self, you're more likely to make a healthier choice.

So, as Richard says, if you're a candy bar company, we know that we might want to use the opposite of that and get to immediate gratification, but if we're trying to live a healthier life or eat lower calorie foods, planning that a little further in advance, you're much more likely to make the decision that you want to make when it's not immediate.

Jordan Harbinger: Okay. The book also makes an attempt to justify the abomination known as the Starbucks Pumpkin Spice Latte. I would love to know what's going on here. I think a lot of people would like to know why these are so popular, because for me, they don't do what they're obviously doing for other people. And this is obviously multi, multi multimillion dollar flavor sub-brand for them because you can find candy flavored with this.

There's the home version, there's the tea version, there's the [00:20:00] whatever version, there's the sweetened unsweetened. I mean, this is a whole thing. And yes, it's seasonal. Okay, fine. But there's obviously, there's gotta be more to it than that.

MichaelAaron Flicker: Yeah. And the numbers are actually quite staggering. Uh, 200 million pumpkin spice lattes were sold in the first 10 years, and it was an immediate hit the first year they did it.

But now it's almost like a mini holiday Jordan, when they launch pumpkin spice latte, they can project the sales in regions and in individual markets within a few percent of what it's going to do. The financial analysts that were just looking through. The most recent quarterly earnings report from Starbucks said, this may be a beverage, but it's actually like a financial instrument.

When Starbucks puts it out, it will deliver the financial results they want. And so there's absolutely an element of scarcity. This then it's going to be outta market, then into market. But Richard, we found talking about the [00:21:00] nostalgia that it wells up in people as something they really hit on in a big way.

Richard Shotton: Yeah, there's probably two elements to Starbucks. I think the crucial thing is it's limited supply. There's a British writer called GK Chesney, famously said, the way to make anyone love anything is to make them realize it can be lost. Now, I wouldn't underestimate the power of running the pumpkin spice latte just for a month or two.

I cannot believe that if they'd run it all year round, this thing would still be generating billions in revenue. There's definitely experiments to back this up. There's a, a lovely study from Steven. We at the University of Virginia and gives people this glass jar of cookies and some people, he comes into the room with a glass jar and the cookies are spilling out the top.

It's completely full. There's 10 of them and they rate how much they're prepared to pay for the cookies. He then gets completely new group of people, goes in with the same batch of cookies, the [00:22:00] same glass jar, but there's only two cookies in the bottom. And when that group rate how much prepared to pay for the cookies, they come back with our notes.

I think it's 20 or 30% higher rating. It is a fundamental of human nature that we want what we can't have. So I would say the core reason for pumpkin spice latte success is the fact that they limit supply. That is something that far more brands could replicate. You know, most people, they have a successful product.

They're just trying to maximize the immediate sales.

Jordan Harbinger: Yeah.

Richard Shotton: But if you want long-term value creation, you want to be taking this product away before people have say to themselves.

Jordan Harbinger: By the way, guys, you said it's available for a couple months. When do you think, without looking, when do you think they released the pumpkin spice latte?

Which by the way, is known as the PSL in every document I've looked at, I've looked at so far that it's got its own. A brief

Richard Shotton: middle

MichaelAaron Flicker: of

Richard Shotton: August.

Jordan Harbinger: Yeah, the end of August. Okay. That's pretty good. That thing has been out since summertime.

Richard Shotton: Well, you could argue [00:23:00] they are falling for the mistake that for 20 years they've been avoiding.

Jordan Harbinger: Yeah.

Richard Shotton: You know that if they get greed and if they keep on increasing the length, it's on sale. There will be problems. They will undermine their cash cow.

Jordan Harbinger: This is like how Black Friday now starts on Wednesday, but then goes through Cyber Monday and then the following week, and then it's like some businesses are like Black Friday in July, and you're like, so it's just whenever then.

Right. I don't have to actually rush. It's just like a whenever, and you're like, yeah, okay, fine.

MichaelAaron Flicker: Well, I think when consumers start acting that way, brands will stop performing that way. Yeah. But so long as Black Friday and July yields results, I think you're going to see brands continue to flock to it. I mean, Amazon Prime days.

Are made up holidays?

Jordan Harbinger: Yes.

MichaelAaron Flicker: On random days actually. Uh, notably on low sales days, they created Amazon Prime days and people will shop if they think there's a scarcity and opportunity to get a better deal than they otherwise could get.

Jordan Harbinger: Yes. [00:24:00] And what you're doing is you're getting Amazon branded batteries at 14% off and everything else is the same price, but somehow I've got like outdoor furniture now because it was on sale.

The other lever that Starbucks is pulling with the PSL is nostalgia. Tell me about that. Because although it didn't exist when I was a kid, it feels like it existed when I was a kid, even though it, of course it didn't. Starbucks didn't exist when I was a kid, so I don't know exactly how they're doing this.

Explain.

Richard Shotton: So nostalgia is something that far more businesses could apply. There's less research on nostalgia than there is around principles like scarcity or the gold dilution effect. But one of the academics that worked in this area is someone called Janine Lasa. So she's at the gr NOL School of Management and in 2004, she gets people and she shows in this booklet with various different products in, and for one of the ads, she varies the copy.[00:25:00]

So sometimes it says to people, it's a Kodak ad. You know, remember a special moment in your past. Other people see the same booklet, but it says, you know, think about a special moment that's about to come. And what Las Leader finds is that if you get people to think about the past, you get people to think about special moment long ago, they're far less price sensitive than if they're just thinking about any old special moment.

And last leader's argument is the, there are two Broadways for people to think. They can think about money or they can think about social connection, and she says, when you start getting people to think about their past, especially their childhood, it gets them thinking more and more about social connection and the impact and importance of money doesn't quite disappear, but it's attenuated decreases and therefore they become less price sensitive.

Creating this kind of mix of, you know, nostalgic childhood, holiday linked food flavors is a very sensible tactic from Starbucks [00:26:00] perspective.

Jordan Harbinger: It's amazing that expensive things magically seem better even when they're not, which makes this a perfect time to pay the bills. We'll be right back. This episode is sponsored in part by SimpliSafe.

True Story. Jen's cousin and their family left the house around 7:00 PM for a school event on a normal weeknight, and then they get a phone notification break in at the house. They had sensors, but they had no professional monitoring, so it was basically, hey, something bad is happening, and they're struck trying to react from a parking lot.

In the time it took to call the police and process the alert, the burglars had already smashed in through the backyard glass door, ripped out their safe in the bedroom closet. Most obvious place to put a safe, by the way. And were gone with over 30 grand in under 10 minutes. So don't keep 30 grand in your house, by the way.

But that's why I like SimpliSafe. It's not just a camera that records the crime for later. It's designed to help stop it while it's happening. They're AI powered. Outdoor cameras can spot real threats and immediately alert live monitoring agents. And those agents can intervene while the intruder is still outside.

Talk to them through the camera, let 'em know they're being watched and the police are on the way, and if needed, hit 'em with a siren on a spotlight. It's proactive, not passive. And [00:27:00] after hearing that story, proactive is a good idea.

Jen Harbinger: Right now you can get 50% off any new system this month only. It's a great time to upgrade to security that actually helps stop crime before it starts.

Go to simplisafe.com/jordan right now to claim your discount. That's simplisafe.com/jordan.

Jordan Harbinger: This episode is also sponsored by Rag and Bone. If you're in the market for really solid denim and jackets too, you should check out Rag and Bone, especially their infused denim. I'm big on comfort these days.

These jeans with a rare pair that felt broken in immediately. They've got stretch where you want it, structure where you need it, and they're insanely comfortable without feeling flimsy. You can tell they're high quality the second you put 'em on. Another thing I like is the fit lineup. Infuse comes in a bunch of options.

Slim, straight, athletic, relaxed, so whatever your style is, they gotta a cut that works and they're the kind of jeans you can throw on with basically anything in your closet and still look put together. And the washes are legit. I went with a darker wash. The color has this rich dimensional look to it.

Rag and Bone does this proprietary multi-step over D process, so they actually get better the more you wear 'em. I've [00:28:00] even gotten compliments like, wow, where'd you get those? Which basically never happens with, well, anything that I wear these days, 'cause I'm old because normally you're choosing jeans that look great or jeans that last with rag and bone.

You get both. They've spent 20 years obsessing over denim. That improves over time and you can feel that attention to detail right away.

Jen Harbinger: It's time to upgrade your denim with Rag and Bone for a limited time. Our listeners get 20% off their entire order with code JORDAN at rag-bone.com. That's 20% off at rag-bone.com with promo code JORDAN, when they ask where you heard about them, please support our show and let them know we sent you.

Jordan Harbinger: Don't forget about our newsletter. We bit wiser. It is a two minute read every Wednesday. It is very practical, applicable. You can use it right away. It's a nugget of wisdom from one of our thousand plus episodes and it's a great companion to the show.

Jordan harbinger.com/news is where you can find it. Now, back to Richard Shotton and MichaelAaron Flicker. It's tough to do this with every brand. Like how would I do this? You gotta release the podcast on vinyl. You can only share it if you have a dual tape deck so you can give a [00:29:00] copy to your friend.

Like the last time I used something like that was I was copying Michael Jackson's bad album, I think, which is still fire, even with tape his in the background. But like not every brand can do this, right? It's tricky

Richard Shotton: and they don't need to. So if you are a podcaster and you are free to air, well, a bias and experiment about price sensitivity is irrelevant,

Jordan Harbinger: right?

Richard Shotton: But if you are, what are the 90% of FMCG or CPG products that has to sell? Well then you do want to be interested in price sensitivity. And it doesn't have to be as direct as in the Las Alta study. In the book we talk about Oreos. You know, they do a, a promotion where they tied up with Pac-Man. That's a brilliant approach.

That's cool because Pac-Man is probably a hell of a lot cheaper than buying a, a modern computer game. And it gets people to think about their childhood.

Jordan Harbinger: Imagine how much it costs a license. Pac-Man from Atari, they're like, somebody wants to license Pac-Man. And they're like, yeah, it was that, or Sonic the Hedgehog.

And it's like one was a million dollars and the other was like, go ahead. What? Whatever, bro. [00:30:00] You know? And we just, we're just stoked. You want to use it?

Richard Shotton: Just send us a photo of you doing

Jordan Harbinger: it. Hey, yeah, give us some free Oreos was probably the cost of licensing Pac-Man 45 years or whatever after the inception of the brand.

Yeah. Disney's really good at this kind of stuff too, not just with the nostalgia. I mean, they're the masters of this, but they used to do this thing where I, I grew up adjacent to a bunch of rich kids who would get everything, you know, that they wanted kind of. And I remember when videos would come out of new movies, like The Lion King was first available on VHS.

You couldn't rent it. 'cause it was, even though Blockbuster had like a hundred copies, they were all gone for the first like six months that they were there. Uh, unless you got super lucky or your friend worked there, but people could buy them. But if you wanted to buy that VHS tape. It was like a hundred dollars in nineties money.

Okay. So I don't know what that is now. $200, $300. Like it's insane. And my friend's moms go and buy these things. And I'm like, how are you getting this? Where are you getting it? And it's like, oh, if you're willing to pay [00:31:00] out the nose, you can have it. But then what was really interesting was I was like, oh, do you have this?

And they're like, no, you can't buy that. And I'm like, what do you mean you can't buy that? It came out five years ago. And they're like, yeah, if you want, I don't know, Fantasia or something. The Little Mermaid. You have to wait like 10 months or possibly even two, three years for them to make another batch of these VHS tapes.

Or you're buying it on, I don't even know where you would buy a used video back in the day, like some thrift store. You'd get a lucky find because it wasn't available. They stopped making it. It was like taking a book outta print and then being like, you can't have it, but it'll be back in three years.

MichaelAaron Flicker: And to increase the sexiness of this Jordan, they called it the Disney Vault Uhhuh.

So not to make you feel that they were stealing from you, they manufactured their own scarcity.

Jordan Harbinger: I

MichaelAaron Flicker: see. They created the Disney vault. The video was out of the vault, and then it had to go back. In the point of your story, which I think all listeners can understand, is that sometimes scarcity is truly bullshit real.

Jordan Harbinger: Oh,

MichaelAaron Flicker: [00:32:00] and sometimes that's the point. Sometimes it's to the brand's benefit to limit the availability to drive up cost. Or to drive up interest. And Supreme as a clothing brand was based on the only, the concept that they were going to have. Limited qualities. Yeah. Disney, your example. They're limiting the time that you can buy those videos.

Jordan Harbinger: I assume this doesn't really work in the age of the internet with Disney's Vault because it's like, oh, it's in the vault, fine, I'm going to go steal it. You know? Maybe they limit it from streaming services too. I assume Disney has the power to do that. Uh, but you can't take it off the Pirate Bay. But then again, 0.1% of internet users probably know how to do that stuff.

Right. So maybe it still works. I don't know.

MichaelAaron Flicker: You know, in America, K-Pop Demon hunters was the hottest summertime blockbuster. It was made by Netflix.

Jordan Harbinger: Yes.

MichaelAaron Flicker: But Netflix did not anticipate its success. And they did not have the Halloween costumes that they normally would have. And that was true scarcity. They did not think it was going to be such a blockbuster.

They did not make them. I don't know if this is [00:33:00] factually true, but walking down the streets in New Jersey, the number one homemade costume was K-pop demon hunters. You know? I mean, so there is something to that ability to manufacture it, and sometimes it does occur in the world.

Jordan Harbinger: Don't worry. Every Chinese manufacturer was on it.

They were like, Hey, K-Pop demon hunter. All right. We need like white hair and some glitter, and then we need like a blue hair one and then booty shorts, and then put them all in a plastic bag and then call it K-Pop Demon hunter. Sir, isn't that illegal? Do we care? Not really. Boom, Amazon, and then that thing, you could see, you know, when it's like purchased 89,000 times this week, and I'm like, it's Monday night.

What? Yeah,

MichaelAaron Flicker: it's incredible.

Jordan Harbinger: There is just. The entire Chinese inventory of wigs and like pink booty shorts and whatever else was a, they were running the presses overnight for those things is unbelievable. The demand for that. You frequently mentioned the attention to action gaps, such as like wanting to work out, but you don't, your motivation isn't sufficient.

How do brands work [00:34:00] around this?

Richard Shotton: Yeah, so it's a very common problem. The people intends to change their behavior like they intend to eat healthier or exercise more, but they never quite get round to doing it. And the argument from psychologists is motivation is a necessary but not sufficient condition for behavior change.

What you also need to do is associate whatever behavior you are trying to encourage people to do with a very clear time, place or mood. So essentially you want to create a cure or a a trigger moment. So thinking in the kind of personal example that you mentioned, let's say you want someone to take vitamin D every.

You wouldn't say, just take vitamin D once a day. You'd say, once you've had your first coffee, take vitamin D. There might be no pharmacological reason for taking it after coffee, but by attaching that behavior to a very clear trigger moment, it is much more likely to occur

Jordan Harbinger: because you're not going to forget the coffee, but you're probably going to forget the vitamin D.

Richard Shotton: It's exactly that. The coffee drinking [00:35:00] happens and that moment acts as a catalyst that converts the vague intention to take vitamin D into actual behavior change. So yeah, you need to create this cure or trigger.

Jordan Harbinger: When we were kids, there was a gimme a break, break me off a piece of your Kit Kat, or something like that.

Break me off a piece of the Kit Kat bar, and that was like, oh, you're done with dealing with a-holes at your retail job. Sit down and snap open this thing and then share it with your friend. It is pretty brilliant campaign, I assume worked well for them.

Richard Shotton: Interestingly, and I didn't realize this till Michael and Aaron and I were chatting during the book, that American campaign is completely different from Britain.

In Britain, the line for about 70 years is have a break, have a KitKat.

Jordan Harbinger: Mm.

Richard Shotton: And they've run that line consistently.

Jordan Harbinger: That's even more directly associated with the break.

Richard Shotton: Exactly. So I prefer that simplicity and directness of the British one. It's not that they're talking about how beautiful the KitKat tastes, but there is this very clear association.

You have a tea break, you have a coffee break. You're there with the Kit Kat.

Jordan Harbinger: There's no sharing involved in the British one. I'll point out it's selfish. [00:36:00] Have a break, have a Kit Kat. And if your friend wants some, well, too bad. He should go get his own selfish Brits. What else is new? Um, what, what about, uh, diet Coke?

You mentioned Diet Coke in the book that I just remember. All of the women leaning out the window, looking at some guy digging a hole or whatever and slamming a Diet Coke in the parking lot is that, I probably shouldn't have admitted that, but that's the one. That's the one I remember.

MichaelAaron Flicker: Your memory is spot on.

Decades later. And what they were trying to show everyone was, when it was time to take a break from work, it was time to have a Diet Coke, break, crack open a can of Diet Coke, treat yourself to something indulgent, but not necessarily unhealthy. 'cause it was Diet Coke. That was the pitch, right. Uh, 30 years ago.

But what's fascinating is you remember those women leaning out the window looking at the workmen. Yeah. I don't know if that would fly in today's, uh, in today's advertising culture.

Jordan Harbinger: Maybe not. Yeah, it was. It was probably where the phrase thirsty comes from actually. And then they had Cindy Crawford, I think later 'cause guys started drinking Diet Coke, which I [00:37:00] don't think Coca-Cola really expected.

I think that might have been an afterthought that guys actually were going to start to drink Diet Coke as well. And yeah, Cindy Crawford made sure that we were. Snickers also does this really well. This whole like, Hey, are you hungry? Don't, don't bother with food or anything. Just have a Snickers bar.

Richard Shotton: It's exactly the same principle.

MichaelAaron Flicker: Yeah. And what they do really creatively is the other two. We talked about Kit Kat on a break, diet Coke at a timed break. We're very literal. Snickers is a little bit more creative. And they say not just when you're hungry, but you are not you when you're hangry.

Jordan Harbinger: Oh yeah.

MichaelAaron Flicker: So if you are beyond just being hungry, you actually are not the you you want to be when you're so hungry, you're angry.

They make this campaign, you're not you. They've got amazing, uh, creative. You know, they have Betty White turning into a football player when she's hungry. You know, I mean really great creative. But they're interestingly using this anger from being hungry [00:38:00] as the trigger moment. That can be pretty compelling.

'cause it's a feeling you have inside you. So the next time you are so hungry, you're starting to get angry. That's when you should pull a Snickers bar. So they're using a trigger in a similar way, but slightly different.

Jordan Harbinger: Are they doing anything other than being funny and memorable? Is there anything else going on or you mean also the break association?

But it's, instead of a time, it's a feeling. That's actually, you're right. That's it. Wow. Speaking of humor though, it cuts through the noise. What else does it do? You mentioned in the book it actually can reduce price sensitivity, which I had never heard of.

Richard Shotton: It's a fascinating one in the, you would think all advertisers knew this.

Actually across the world, there has been a reduction in the proportion of ads that try and amuse. So you go back to the 1990s and about 60% of them try to amuse 2023. It's about 35%.

Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. Ads were really funny in the nineties

Richard Shotton: they used to be a lot funnier.

Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. And

Richard Shotton: it's a massive mistake. People notice ads.[00:39:00]

If you put 'em in a good mood, they're more likely to believe what you tell them. And then, yeah, work that I've done with Ben Davies suggests that it also reduces price sensitivity. So we got 821 people, which showed them a series of promotional ads, so maybe like a bottle of Bailey's for $10 or some pizzas and Budweiser for $15.

And every ad people had to rate where they thought it was good value or bad value. We average those scores and then we asked what mood people were in. And what we found is if people were in a good mood, 76% of them. Thought the products were good value. If they're in a bad mood, it was 60%. It's exactly the same product is rated 26% better value if people are in a good mood.

And I think what's happening here is what people should do is just judge and offer on its inherent qualities, the price and the benefits. But what they actually do is they confuse their initial feelings, their internal feelings with what's in front of them. [00:40:00] Some of that positivity they're feeling generally imbues the product in front of them.

So putting people in a good mood is a great commercial tactic.

Jordan Harbinger: This works on me, so well, if I'm at the airport and I have to overpay for a salad, I'm like, Ugh. Yeah, well I'm at the airport. That's how it is. If I'm at Disneyland and I have to overpay for a salad, I'm like, what? It's a Disney salad look, it's got a Mickey shaped crouton in here.

That's fun. And it's like, because I'm in a good mood, but also there's more to it, right? Disney's wowing you with at every step, right? So you feel like, okay, price of it in being this magical place as everything's five times more expensive. The airport doesn't quite have that same sheen. But yeah, when you're in a, when I'm in a good mood, I mean, I literally, I don't want to be in a good mood if I'm shopping for something expensive, because I will often just be like, you know what?

I like these guys. They have a cool logo, and I'm like, what am I doing? No. Yeah. I need to be in a either mediocre mood or even a bad mood when I'm shopping for something expensive. And then I'll have, I'll pull the trigger later when [00:41:00] I don't, it doesn't feel so painful.

MichaelAaron Flicker: You know, we talked earlier about how nostalgia.

Decrease your price sensitivity. Now we're talking about humor. Decreasing your price sensitivity.

Jordan Harbinger: Yeah.

MichaelAaron Flicker: The point is, your emotions have an oversized impact on the decision you're going to make to buy in that moment. And most people do not give that the credit they think they should. You know, most people would say, I'm making a rational choice in this moment, when really what came right before it will have a big impact.

Richard Shotton: It's essentially this idea that what comes first is the intuitive reaction. You know, I feel warm, more cold towards a salesperson. That happens. And then once I've made that decision, then I use all the powers of logic at my disposal to justify that decision to myself. It's the emotional, quick, intuitive reaction that comes first.

Then logic goes afterwards. So what businesses want to be doing is trying to create that snap quick, intuitive positivity, [00:42:00] and a lot of these behavioral science experiments that we discussed in the book. They're all about creating that immediate emotional reaction.

Jordan Harbinger: Apple does this, well, not this particular thing, but a lot of these particular points, it does it well.

Remember the Mac guy, his name was Justin, I forget his name. He's an actor, quite popular now. And then they had the PC guy and it was like a dork versus like a cool kid who was just relaxed and gets it. And the other guy had a suit on and was kind of like a dweeb, and they come out with the iPod, which was not the first MP three player by any stretch, but I remember before it was like the Diamond Rio 128 megabytes.

And you're like, okay, what does that mean? Again, I don't really know what that means. I gotta do some math, I gotta read some online reviews. And then Steve Jobs is like 1000 songs in your pocket and you're like, I need that. I have to get that right now because I want all of the songs. I want to imagine a thousand songs in my pocket and look cool doing it.

They're just really good at making things concrete and understandable and also cool at the same time. I mean, [00:43:00] apple, of course, they, you pay for that and then they pay for that too, whoever they're hiring for this creative stuff. But it works really well.

MichaelAaron Flicker: Yeah. You know, at a very, uh, 30,000 foot level. You can imagine that if someone can get you to imagine it in your brain, you can imagine what a thousand songs in your pocket may be like.

That's a lot more, uh, visual than saying, having you trying to understand what 512 kilobytes really means.

Jordan Harbinger: Sure.

MichaelAaron Flicker: And the study that proves this is really quite interesting. It's Ian Bag at the University of Western Ontario, and he gives study participants a list of 22 word phrases, things like impossible amount, rusty engine, white horse, subtle Fault.

And the game is how many of the 22 word phrases can you remember by the time he finishes reading them. Everybody writes down what they can remember, and the average that they can remember is 23% pretty good. But what's really the striking observation [00:44:00] is that they remember just 9% of the abstract words, things like impossible amount or subtle fault, but they remember 36% of the concrete terms, things like white horse or rusty engine.

So they're four times more effective at remembering those things that they can draw and imagine in their mind. And we see lots of brands do this. M and m says it melts in your mouth, not in your hand. Maxwell Health's coffee says good to the last drop. These are lines that help you remember the thing they want to insert in your brain.

That's what Steve Jobs did so well in that moment. He helped you remember the iPod much more meaningfully, much more concretely than the competitors.

Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. Red Bull gives you wings is another one that you guys mentioned in the book. What Apple also does is they have this, and you touched on this as well, optimal newness, right?

It's something that is exciting but not terrifying. I thought this was quite interesting. 'cause on the iPhone for example, the icon is the old phone and like the touch screen exists, but it also [00:45:00] was made to look like buttons. And the buttons that you would normally dial are still there, the keyboard is still there.

And I, I remember when the keyboard popped up, I was like, okay, this is cool, but you mean to tell me that they redesigned the whole phone and they couldn't figure out an easier way to create input And very likely they do and did have that. And they were like, wait, we're giving people a touchscreen email, MP three mobile device.

Like we need to ramp down the amount of new stuff we're giving people before it turns into Star Trek and they don't want it.

Richard Shotton: Yeah. There's an amazing book by um, Derek Thompson called The Hit Makers. And in it he has this wonderful phrase, which if you wanted to sell something surprising, make it familiar.

And if you want to sell something familiar, make it surprising. Now, to your point, when iPhone launched, it was a massive change. This was a really novel technology to most people. So what they tried to do was give it this aura of familiarity by using very real world everyday symbols. So the delete function was an actual [00:46:00] trashcan.

The notes pages was a legal yellow lined pad.

Jordan Harbinger: It still kind of is.

Richard Shotton: Well now, although it's much less realistic than it once was, it was 3D, you're

Jordan Harbinger: right. It used to have the blue lines,

Richard Shotton: which looked like handwriting. Yeah, that's

Jordan Harbinger: right. I forgot about that.

Richard Shotton: When you deleted a page, it looked like there was a, a tear at the top.

You know, it looked like a bit of paper that'd been pulled off. So that was really useful when it was a shockingly new technology. But what Johnny, ive and Steve Jobs did as, as that iPhone got more familiar, they started making those icons that we still have on our phone now, far less realistic. They became much more abstract.

So it's not just that Apple applied this principle of Optum or newness very well, it's that they kept on applying it in the right way throughout their product lifecycle.

Jordan Harbinger: What is that called when you make something that's digital look analog?

Richard Shotton: Yes. Q amorphism.

Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. I knew that there had to be a term for that because that's, it's so widely used in design.

Uh, you mentioned in the book that Edison, you know, you vetted the light bulb and they made them with [00:47:00] wind shades, which they obviously did not need to emulate gas lamps, which were everywhere because they wanted to make this thing look familiar enough where people weren't like, I don't want this UFO on the road.

I want something that looks normal.

MichaelAaron Flicker: Yeah, I mean, the concern was when you get people to bring electricity into their house and they're replacing these gas lamps, why did they need those wind shades, which became lampshades of the future, and it was to make people more comfortable with them. So it's not just digital tech moving from blackberries with buttons to iPhones with screens even 150 years ago, moving from gas lamps to electricity, we are always asking how can we get, you know, a most advanced version, but yet it's still acceptable to everybody that they're going to want it in their house.

And that's a balancing act. I'd say that's probably more art than science. You had to feel that you could get that amount bought by the consumers. And Edison does it with the lamp and so does Steve Jobs and Johnny Ives.

Jordan Harbinger: One thing I'm shocked still works is the [00:48:00] whole 5 99, not $6. I just refuse to believe most people would care if something is 1 cent more or a dollar more.

And like you said, it's an emotional thing. But it's funny 'cause I've seen things, where was I? Costco I think, and something was literally 17,000 nine hundred and eighty four ninety nine as if it would matter at that price. But apparently it does.

Richard Shotton: Yeah. For all the studies is this is one that's probably been around the longest and you are right to a degree.

If I was to show you two products, one for $10, and then the same thing for 9 99, and I ask you directly, you know, which of these prices would you prefer, which would really change your behavior, you'd probably say, oh, you know, they, they're almost the same. It wouldn't affect me. But that's not how we experience prices in a shop.

We just see one of those prices. And because people are cognitive miers, because they are trying to make quick decisions, what happens is when they see $10, they just remember that price is 10 something. When they see [00:49:00] $9 99, they think of it as nine something. So rather than demand going up by, you know, a tiny, what would it be, 0.1%, it actually goes up by something like 10 or 15%.

It's far more of this kind of stepped effect on demand than pure logic would suggest. So it's often known as this left hand digit bias.

Jordan Harbinger: You know that thing where you intend to keep listening and then you get distracted? Yeah. Let's exploit that for a minute. We'll be right back. This episode is sponsored in part by Progressive.

You chose to hit play on this podcast today. Smart Choice. Progressive loves to help people make smart choices. That's why they offer a tool called Auto Quote Explorer that allows you to compare your progressive car insurance with rates from other companies. So you save time on the research and you can enjoy savings when you choose the best rate for you.

Give it a try after this episode at progressive.com. Progressive casualty insurance company and affiliates not available in all states or situations. Prices vary based on how you buy. I've got Homes.com is the sponsor for this [00:50:00] episode. Homes.com knows what when it comes to home shopping. It's never just about the house or the condo.

It's about the homes. And what makes a home is more than just the house or property. It's the location. It's the neighborhood. If you got kids, it's also schools nearby parks, transportation options. That's why homes.com goes above and beyond. To bring home shoppers, the in-depth information they need to find the right home.

It's so hard not to say home every single time. And when I say in-depth information, I'm talking deep. Each listing features comprehensive information about the neighborhood complete with a video guide. They also have details about local schools with test scores, state rankings, student teacher ratio.

They even have an agent directory with the sales history of each agent. So when it comes to finding a home, not just a house, this is everything you need to know all in one place. homes.com. We've done your homework. If you like this episode of the show, I invite you to do what other smart and considerate listeners do, which is take a moment and support the amazing sponsors who make the show possible.

All of the deals and discounts are searchable and clickable on the website at Jordan harbinger.com/deals. If you [00:51:00] can't remember the name of a sponsor, you can't find the code, email me Jordan@jordanharbinger.com. Happy to surface codes for you. It is that important that you support those who support the show.

Now for the rest of my conversation with Richard Shotton and MichaelAaron Flicker.

Yeah, a lot of these little subtle things tend to make a big difference. One example I thought was really fascinating from the book was when you're shopping online. If something says unavailable versus out of stock.

Because if it says it's unavailable, it's like, oh, we don't have our shit together with our logistics and we couldn't keep enough of these. And you're like, ah, that's annoying of this company not to have this. But if it says out of stock, it's like, sorry, this is just really popular. And then you're like, well, in that case I want you to notify me when this is available again so I can come back really quickly and buy it before it's out of stock again.

But yeah, like I was trying to buy a dry bag from a company and it was like outta stock and I emailed them. I was like, when is this back in? And I looked, it's so funny 'cause it was, this was last week, I had another dry bag from another place and it was unavailable and I was [00:52:00] like, idiots. You know, like it was like, come on man, these can't be that popular.

It's a dry bag. And the other one, I was like, well, if this is so popular, I obviously want this one. So I emailed the company and they're like, actually, they're going to be back in stock tomorrow. Here's the link, you can buy it right now. So I did, and it, it was just the language that made the difference,

MichaelAaron Flicker: and I think that's the underscore of what we wanted to communicate to people.

Even a single word choice can imply it was the brand's fault, or it's so popular that you should want it too. It taps into one of the most powerful biases in behavioral science called social proof. The idea that lots of other people are doing it. And so you would be, you know, you should follow that too.

One word can make a big difference. And so Jordan Y's example really shows that every word that you choose as a brand makes a big difference,

Jordan Harbinger: even if the words are not real at all. Tell me about Haagen Dazs, which I thought the whole time was a European, I don't know, Hungarian ice cream or something, and it turns out it's from the Bronx.

I feel tricked.

MichaelAaron Flicker: They had [00:53:00] wanted you to feel that way.

Jordan Harbinger: Okay.

MichaelAaron Flicker: They really want it to launch the brand as if it was a Danish brand. They have a map of Denmark on the original packaging. The fact that there is no, um, lats over, as in Danish didn't even matter. It was

Jordan Harbinger: no

MichaelAaron Flicker: foreign to the American audience, and that was enough to increase its perceived value.

I think that fact that they wanted to create, uh, something that felt more foreign and more premium, they were able to do through language and through packaging.

Jordan Harbinger: There's a lot of brands that still do this. It's not because it seems very eighties to be like, Ooh, this is French, so it's fancy, you know, like Evian, right?

But I mean Atari, that's clearly a Japanese name. It's a California company from right here.

Richard Shotton: But the argument, I think with the Haaz is what we expect affects our actual experience for products. You know, we talked about it right at the beginning with the healthy food label. You have an assumption that something is healthy, you assume it's going to be, uh, worst [00:54:00] tasting, and that expectation affects your actual experience.

And it's just the same. By wrapping your product in this sophisticated Danish imagery, it sets up expectations about quality and sophistication. It will change how they actually experience that product. Now, I think when this was done back in the 1950s by a tiny little company, it probably was, you know, acceptable.

I don't think we'd recommend any massive brand did this today because it's at heart deceitful. But the underlying point. That the expectations you set up will affect the experience of the products. That's something that I think lots of people can learn from.

Jordan Harbinger: I hear you on the brands, but doesn't Starbucks make me say grande instead of large or medium or whatever.

So I don't know. They're getting away with it kind of. I still say medium, and they know what I mean. They don't gimme any guff anymore.

MichaelAaron Flicker: They're threading the needle there. They're implying Italian heritage. They're implying the greatness of where a great coffee comes from without telling you, they're an [00:55:00] Italian coffee brand.

So it's an interesting example you raised because they're really right on the line by using Italian words, but not saying they're Italian. They didn't put a map of Italy on the cup.

Richard Shotton: So I think Michael Aaron's right? Starbucks I think are in the kind of right side of that ethical gray zone. The original Haaz.

Bit more dubious.

Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. Interesting. They do this with products, though, not even just brands. Isn't Chilean sea bass called Tooth Fish, which is gross and not something I want to eat. Chilean sea bass though. Yes, I'll pay $40 for a small piece. Why not?

MichaelAaron Flicker: I'm calling in today from Argentina. Last night on the dinner menu was Patagonian tooth fish.

Jordan Harbinger: Oof.

MichaelAaron Flicker: Patagonian tooth fish was not the appealing choice on the whole menu. Uh, but we were in Patagonia,

Jordan Harbinger: right?

MichaelAaron Flicker: The story comes from the late 1970s, an American fish importers named Lee Lance, and he has discovered Patagonian tooth fish and he wants to bring it into the US restaurant scene, but [00:56:00] nobody is ordering it.

And he believes the taste profile's, right? It's a white fish, it's flaky, but yet firm. It's got all the right things to make it a winner. And he comes up with the same type of insight that we've talked about before. In the, in the episode, he says, I wonder if the name is really hurting the overall sales.

And so he invented a new name, Chilean Sea Bass. Like that. They lead in the 1990s to a 30 fold increase in consumption of Chilean sea bass alone. Wow. It's really incredible that one word can really make that difference. And in the book we talk about all these other fishy tails. Jordan Dolphin fish was historically called dolphin fish reminds American Buyers of Flipper.

They rebranded in Mahi mahi and it does great.

Jordan Harbinger: Ah,

MichaelAaron Flicker: so there's a bunch of examples like that.

Jordan Harbinger: That's interesting. Are there limits to that? Does, has this ever blown up in a brand's face where they're like, let's name it this, and then it's not [00:57:00] that and people get upset?

Richard Shotton: I mean, I think generally with a brand, there are the occasional dubious ones like Har Andaz, but most of the time there is no absolute term that you need to have for a brand.

So you've got amazing scope to pick things with, with positive connotations and still stay reasonably honest.

MichaelAaron Flicker: In American politics, there was a big debate over an inheritance tax and you know, one party, the left had established it as an estate tax, and when it's called the estate tax, 68% of people oppose it.

When the Republicans rebranded the death tax, 10% increased. 78% of people oppose it. So it may not be a brand that's naming it, but just the thing that it gets named and it gets hooked as it gets remembered as can have a big difference and big impact on how people feel about it.

Jordan Harbinger: That kind of branding or Unbranding works really well.

You hear about that a lot. Death panels, not [00:58:00] insurance or whatever it was like if it was a death panel, they're going to decide if you die. And it's like that's what insurance companies do now, by the way. Um, yeah, this, it's always so fascinating. I want to move on to some specific brands. I know we have very little time left, but I want to keep going here.

Red Bull, the world leader in energy drinks, they have this very specific can size that used to not be used for anything else. Now, other energy drinks I see use it, even coffee uses it. Coincidentally, the best can for a dick pic comparison or so I've been told. But, but uh, yeah, this whole, the idea, we already talked about them before they give you wings,

Richard Shotton: so, so the big thing with Red Bull is they're applying this principle of price relativity.

When we are trying to work out what a fair price to pay for a product is, we don't think about the benefits we'll get. And then think about what's a fair price to pay per single benefit. What we do instead is construct this mental comparison set and we think, well, if this new product is more than something similar, it's bad value.

If [00:59:00] it's less than something similar, it's good value. This idea that pricing is relative rather than absolute was harnessed brilliantly by Red Bull because what 99.9% of marketers would've done is launch Red Bull in a can that is the same size as Coca-Cola or Fanta, or any other drink.

Jordan Harbinger: Yes.

Richard Shotton: And if they'd done that, that would've been the comparison set and people would've been unhappy paying much of a premium.

But what Red Bull did, and Rory Southern talks about this brilliantly, is they shrunk the can. They put it in a much taller, thinner can, and because it just looks completely different from other SOPs, drinks. It made Red Bull into this completely new category and there was no comparison with soft drinks any longer.

The value people were prepared to play became much more free floating. So change the comparison there and you change the willingness to pay.

Jordan Harbinger: Also, I think people almost like things that are more expensive because you expect it to be better. Is there any truth to that?

Richard Shotton: Absolutely. [01:00:00] So there's a Stanford psychological called Baba shiv and he's shown the, we assume high priced items are high quality.

It's a very simple study, gets some Americans, serves them five different bottles of wine, and I'm stressing the word bottles. But the twist in the experiment is there's only four different liquids. So people begin the experiment and they have a little sip from the first bottle that is prominently labeled $5, and they say it's quite a nice merlo.

Couple of minutes later, they are having a sample from a supposed $45 bottle, but what they're actually doing is drinking exactly the same liquid. And when they drink it thinking it's super expensive, they rate it at 77 0% better than when they think it comes out of a $5 bottle. So people assume that high price equals high quality, and as we've discussed again and again and again, those expectations affect the actual experience.

Jordan Harbinger: That's interesting. Yeah. The wine thing is always, they've done so many of those where it's like, oh, these [01:01:00] seven wine experts all think this is amazing. And then they're like, you know, two buck chuck from Trader Joe's. Basically, the whole thing is kind of a, a farce, but price can signal or will signal quality.

Although I, again, I find it's often an illusion, not just with wine. I don't know anything about wine, but you ever buy anything off Instagram, like clothing or products and you're like, wait, this was marketed so well. And then you're like, but this is expensive. It's a hundred dollars, like Special forces sweater or whatever, $200.

And then you, you realize, I talked to my buddy who's a clothing manufacturer. He goes, yeah, what they're doing is they're spending $150,000 on ads. So this sweater, you could probably get off Temu or something for like $28. It's not that special. Really, the wool involved, like, it's like slightly above, uh, an Amazon, you know, generic brand, but it's not a $200 sweater.

It's just that they spent so much money to sell you that, that they have to make it back. And so you're not actually getting the quality, you're getting the Instagram markup. And I've [01:02:00] fallen for this so many times, right, because they're, they're just bombarding me with this stuff. But the illusion is that they've invested in the quality, right?

It's been trained by the Special Air service. Uh, you know, they've run it through the ringer and it's like, nah, it's just a special air service guy in the photo. That's really all it is.

MichaelAaron Flicker: And it's interesting because brands have been doing this for decades, maybe many decades. Uh, you know, when you see a sports team sponsored by a brand, all of a sudden you think, uh, this brand of socks, it must be of higher quality.

Yeah. We started with Red Bull. When Red Bull has Felix Baumgartner jump off a helium balloon 24 miles in the stratosphere and free fall back to Earth.

Jordan Harbinger: Now how much Red Bull did this man drink? That's amazing.

MichaelAaron Flicker: And how much money does Red Bull must make in order to support stunts like this? Right. And so it builds this aura of just how successful the brand is, even if, as you say, they spent the vast majority of their money to make that happen.